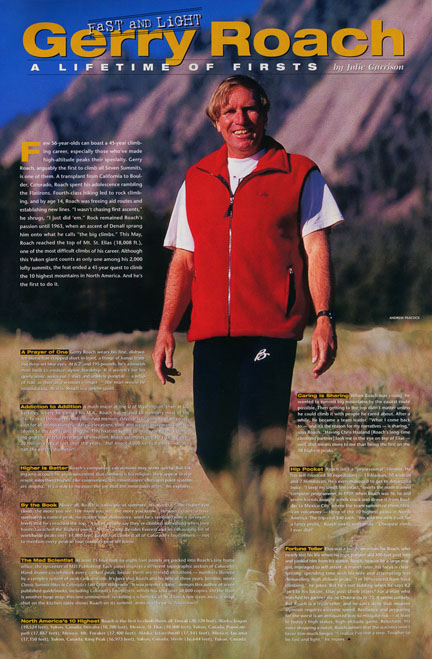

Gerry Roach wears his fine, dishwater-blond hair cropped short in front, a fringe of bangs framing deep-set blue eyes.

At 6’ 2” and 195 pounds, he’s a bearish man built to endure alpine hardship. If it weren’t for his

goofy smile, worn-out T-shirt and unlikely ponytail, the man would be intimidating. As it is, Roach is a gentle giant.

– Julie Garrison |

Fast and Light

Gerry Roach – A lifetime of Firsts

by Julie Garrison – From Rock and Ice #102, August 2000 |

|

Few 56-year-olds can boast a 45-year climbing career, especially those who’ve made high-altitude peaks their specialty.

Gerry Roach, arguably the first to climb all Seven Summits, is one of them. A transplant from California to

Boulder, Colorado, Roach spent his adolescence rambling the Flatirons. Fourth-class hiking led to rock climbing,

and by age 14, Roach was freeing aid routes and establishing new lines. “I wasn’t chasing first

ascents,” he shrugs, “I just did ’em.” Rock remained Roach’s passion until 1963,

when an ascent of Denali sprang him onto what he calls “the big climbs.” This May, Roach reached

the top of Mt. St. Elias (18,008 ft.), one of the most difficult climbs of his career.

Although this Yukon giant counts as only one among his 2,000 lofty summits, the feat ended a 41-year quest to climb

the 10 highest mountains in North America. And he’s the first to do it.

|

A Prayer of One

Gerry Roach wears his fine, dishwater-blond hair cropped short in front, a fringe of bangs framing deep-set blue eyes.

At 6’ 2” and 195 pounds, he’s a bearish man built to endure alpine hardship. If it weren’t for his

goofy smile, worn-out T-shirt and unlikely ponytail – a whip of hair as thin as a woman’s finger –

the man would be intimidating. As it is, Roach is a gentle giant.

|

Addiction to Addition

A math major at the U of Washington, then at UC Berkeley, where he earned his M.A., Roach has related to numbers most of his life.

To read through his self-published memoir, Odyssey, is to glimpse at an obsession for all things numeric:

dates, elevations, time, and weight increments, prices (down to the cent!) and lengths. This fixation seems to motivate

Roach’s climbing goals. In playful reverence to elevation, Roach estimates that he’s gained over

20 million vertical feet over the years. “Ha! About 4,000 vertical miles – That’s half the

earth’s diameter!”

|

Higher is Better

Roach’s compulsive calculations may seem quirky. But taking into account his pronouncement that climbing is his religion,

they appear to represent something higher. Like communion, this mountaineer’s lists and point systems are dogma.

“It’s a way to measure the joy that the mountains offer,” he explains.

|

By the Book

Above all, Roach is a disciple of summits. His mantra: “The higher you climb, the more you see.

The more you see, the more you know.” He won’t claim to have summited a peak, no matter how diminutive,

until he’s verified (with a surveyor’s level) that he’s reached the top. “A lot of people

say they’ve climbed something when they haven’t reached the highest point,” he says sadly.

Besides Everest and an exhausting list of worldwide peaks over 14,000 feet, Roach has climbed all of Colorado’s

fourteeners – not to mention every peak in four counties near his home.

|

The Mad Scientist

At least 15 four-foot-by-eight-foot panels are packed into Roach’s tiny home office, the epicenter of

Summit Sight. Each panel displays a different topographic section of Colorado. Hand-drawn circles mark every

ranked peak; beside them are revised elevations – numbers derived by a complex system of peak rank and rise.

It’s here that Roach and his wife of three years, Jennifer, wrote Classic Summit Hikes in Colorado’s

Lost Creek Wilderness. “It was Jennifer’s baby,” demurs this author of seven published guidebooks,

including Colorado’s Fourteeners, which has sold over 50,000 copies. On the floor is another huge map,

this one unmounted, revealing a schematic of St. Elias. A few steps away, a snap-shot on the kitchen table shows Roach

on its summit, arms overhead – Touchdown!

|

North America’s 10 Highest

Roach is the first to climb them all: Denali (20,320 feet), Alaska; Logan (19,524 feet), Yukon, Canada;

Orizaba (18,700 feet), Mexico; St. Elias (18,008 feet), Alaska and Yukon, Canada; Popocatepetl (17,887 feet),

Mexico; Mt. Foraker (17,400 feet), Alaska; Iztaccihuatl (17,343 feet), Mexico; Lucania (17,150 feet), Yukon, Canada;

King Peak (16,973 feet), Yukon, Canada; Steele (16,644 feet), Yukon, Canada.

|

Caring is Sharing

When Roach was young, he wanted to summit big mountains by the easiest route possible. Then getting to the top

didn’t matter unless he could climb it with people he cared about. After a while, he became a team leader.

“What I come back to – and it’s the reason for my narratives – is sharing,”

says Roach. “Having a climbing partner look me in the eye on top of a peak

– well, that means more to me than being the first on the 10 highest peaks.”

|

Hip Pocket

Roach isn’t a “professional” climber. He has self-financed 30 expeditions – 13 Alaskan,

10 Andean and 7 Himalayan. He’s even managed to get to Antarctica twice. “I keep my credit line intact,”

snorts the math-trained computer programmer. In 1959, when Roach was 16, he and seven friends bought a milk truck

and drove it from Boulder to Mexico City, where the team summited three Mexican volcanoes –

three of the 10 highest peaks in North America. The trip cost $40 each. “We sold the milk truck for a fancy

profit,” Roach swells with pride. “Cheapest climb I ever did!”

|

Fortune Teller

Elias was a tough mountain for Roach, who nearly lost his life when his rope partner slid 100 feet past him and

yanked him from his stance. Roach, heavier by a large margin, managed to self arrest. A month later,

his focus is clear: writing, spending time with his wife and attempting less demanding, high altitude peaks.

“I’m 10% retired from hard climbing,” he jokes. But he’s not kidding when he says K2

isn’t in his future. Elias post-climb jitters? For a man who watched his partner die on Chacraraju in

’71, it seems unlikely. But Roach is a truth-teller, and he can’t deny that modern alpinism requires

extreme speed. Resilience and preparing for the worst is an antiquated way to mitigate risk –

at least in today’s high-stakes, high-altitude game. Reluctant, his voice dropping a notch,

Roach admits that the statistics won’t favor him much longer. “I realize I’ve lost a step.

Tougher to be fast and light,” he muses.

|

|

– Julie Garrison |