The Great Basin is a blank spot in our minds.

– John Hart - from his Sierra Club Totebook: Hiking the Great Basin |

Currant Mountain – 11,513 feet

Rising from the desert floor in eastern Nevada like a misplaced juggernauut, Currant Mountain’s

pale, clean, limestone walls soar above red and green foothills to the highpoint of the White Pine Range.

Snow pockets persist into June and July to enhance the peak’s charisma.

The long north-south summit ridge boasts many summits, but the highest requires a stiff climb,

and sees only a few bootsoles each year. |

|

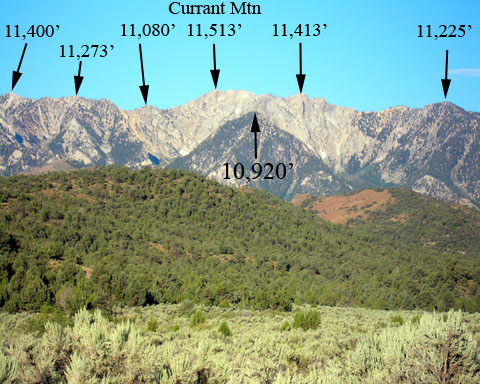

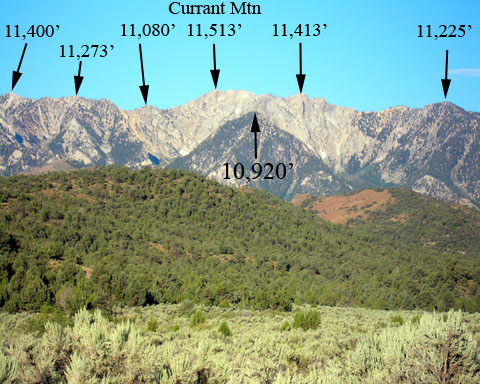

Currant Mountain from the east

The route goes south up a small valley under the summit cliffs, climbs west up the southernmost side gulch,

climbs out of that gulch to reach the upper northeast ridge of Point 11,273, then goes north along the summit ridge |

|

Currant Bristlecone near 10,500 feet |

|

Jennifer in a bristlecone arch near Point 11,273 |

|

A friendly bristlecone giant near the summit |

|

Currant’s final summit steps over limestone and basalt |

|

A nicely preserved benchmark |

|

Looking across at the limestone catwalk and it’s exposed downclimb

shows a possible airy traverse northward from the summit block |

|

Even on the summit, nature’s artistic mix of plant life and rock art are eye pleasing |

|

Natural mosiac patterns in the summit blocks |

|

Gargantuan legs of bristlecone ancients in a grove below the summit ridge |

| Gerry took the above photos on 8/21/05. |

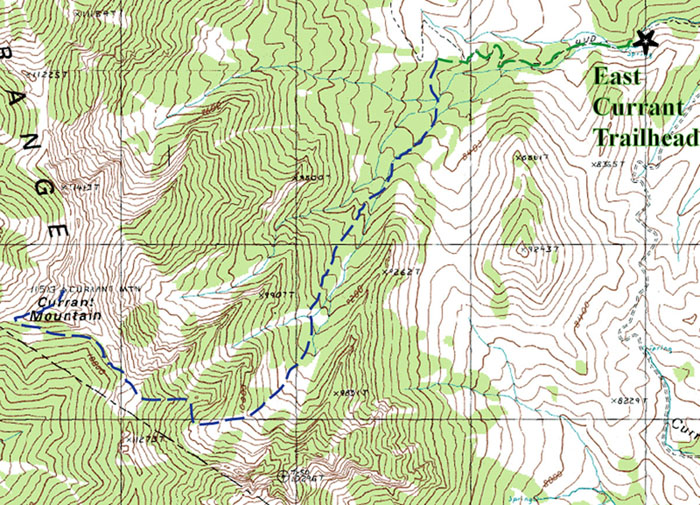

USGS 7.5’ Quadrangle: Currant Mountain |

Southeast Ridge – 7.4 miles RT, 3,713 feet net & 4,193’ total, Class 2+

| We believe that this is the easiest route on the east side of Currant Mountain. This hike begins with a walk up a road,

followed by a bushwhack up a small valley often choked with avalanche debris, then a steep scamper up loose rock slopes

studded with magnificent Bristlecone Pines to an airy summit ridge. This arduous outing has fooled some hikers

due to it’s difficult route finding, steep slopes, and loose footing.

Start at the East Currant Trailhead southwest of Ely, Nevada. |

| From the trailhead, walk west on the old road and cross the stream three times. The middle crossing is not really a crossing,

just a place where the water runs down the road next to the rocks on the right. Continue on the road for 0.5 mile

to a sharp switchback to the north (right). At this point, you are in the wash draining the southeast side of the mountain.

Counting the first turn where the road leaves the wash, walk up the road to the fifth switchback, which has a good view of

the upper mountain and the route ahead. It’s a good idea to study the route while you can still see it. Impressive slabs

rise to a summit ridge which has many summits. The highest is the southernmost on the solid rock summit ridge.

Southeast and well below the main summit is a small, hard-to-see valley rising to the southwest.

Rising to the west above this valley, you can see a wide, rough-cut bowl sweeping up to small saddles on either side of

tiny Point 11,080, which is the first sub summit south of the main summit.

Other sources direct you to ascend this bowl, but it does not hold the easiest route. The route described here is in the

next significant bowl to the south, which caps the upper end of the small, hard-to-see valley. The top of this bowl is

Point 11,273, which is the second sub summit south of the main summit. |

| Leaving the road at the fifth switchback, your next task is to re-enter the large wash to the south,

which will lead you into the small, hard-to-see valley. A direct descent to the south from the fifth switchback is a

daunting bushwhack. Appealing at first, a faint, unused road contours to the west, but alas, it ends after 50 yards.

For the easiest route, walk west up the grassy hill for 200 yards along the edge of the hill dropping to the south,

and look sharp for another faint, unused road that angles southwest then southeast down into the wash. Neither of the

faint, unused roads show on the USGS quadrangle. If you can’t find the upper road, just bushwhack down into the

large drainage, which is filled with lots of loose alleuvium. Either way, turn south-southwest (right) and follow the drainage

upward for 0.4 mile into the small, hard-to-see valley. If you find the best line, the walking is easy - almost Class 1. |

| Look for, and pass below the first bowl to the west. Beyond that, cross an avalanch path below another swath.

Continue along the western edge of avalanch debris in the small valley as it gradually turns to the west.

At 10,400 feet, when the upper valley sweeps above you in a nearly continuous array of slabs, turn to the northwest,

climb a steep slope between large, gnarled Bristlecone (Class 2+), and reach a small saddle on the northeast ridge of Point 11,273 at 10,600 feet.

Climb west up this steep, rounded ridge through more trophy trees and reach the south ridge of Currant Mountain

at 11,160 feet, just north of the rocky top of Point 11,273. The steepest part of your ascent is over, and you can look north at the

remaining challenge. Turn north, and descend easily to the 11,000-foot saddle between Point 11,273 and Point 11,080. From this saddle,

you can peer down the first bowl and be glad that you didn’t come up that way. |

| Your next task is the summit massif of Currant Mountain, which presents complex east and south faces.

We do not recommend a direct ascent from the 11,000-foot saddle up the east face. For the easiest route, contour northwest

under the rocks of Point 11,080, then angle west up the scree under the rocks on Currant’s east face. Reach Currant’s

west ridge at 11,360 near the highest trees, turn east (right) and follow this ridge to the summit.

The last 100 yards take you over solid rock, which is adorned with intricate patterns. |